Going With the Flow

When you step into Dr. Erkang Hu’s downtown Bellevue acupuncture clinic (kangacupunctureherbs.com), it feels as if someone hit the Pause button; it’s a place for healing. For Dr. Hu, who grew up in Beijing, this atmosphere is second nature.

Her parents were both practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). She grew up in a household where neighbors regularly knocked on the door with a cough or stomach pain, asking her parents to read their pulse or check their tongue for a quick assessment. Then they’d walk away with a handwritten herbal prescription to take to the nearest apothecary.

Her parents were both practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). She grew up in a household where neighbors regularly knocked on the door with a cough or stomach pain, asking her parents to read their pulse or check their tongue for a quick assessment. Then they’d walk away with a handwritten herbal prescription to take to the nearest apothecary.

Despite this upbringing, Dr. Hu pursued a degree in Western medicine at a university in northeastern China. She trained in internal medicine, but the rigidity of the system left her restless; it seemed that human connection was secondary to protocols.

In 1993, encouraged by her father—then China’s first director of the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine—Dr. Hu moved to the United States, where she initially considered business school. But after seeing how saturated that field was, she enrolled in a four-year master’s program in traditional Chinese medicine in Seattle and returned to the medicine that had shaped her childhood.

After graduating, Dr. Hu immediately opened her own practice. Her early patients were mostly white Americans—curious, open-minded and eager for relief. Over time her clientele has expanded, yet she still finds it remarkable that many Chinese families in the US have never tried the medicine that’s shaped Chinese culture for centuries.

Western medicine is focused on quick fixes, but TCM believes that sustainable healing takes patience. Dr. Hu’s philosophy about that difference is disarmingly simple. Most of her work centers around helping the body move what is stuck—pain, tension, stagnation—and teaching patients that small, daily choices shape their well-being.Warm food over cold. Cooked meals in winter. No iced drinks. Ginger tea. Heat for menstrual cramps. Gentle self-massage to encourage the movement of qi.

Western medicine is focused on quick fixes, but TCM believes that sustainable healing takes patience. Dr. Hu’s philosophy about that difference is disarmingly simple. Most of her work centers around helping the body move what is stuck—pain, tension, stagnation—and teaching patients that small, daily choices shape their well-being.Warm food over cold. Cooked meals in winter. No iced drinks. Ginger tea. Heat for menstrual cramps. Gentle self-massage to encourage the movement of qi.

These aren’t exotic ideas; they may be things you already do instinctually.

As she talks about her work, Dr. Hu radiates a quiet conviction: that health is not just the absence of symptoms but the presence of balance. Her experience with both Western and Chinese medicine gives her a unique view on how to bridge the two—she understands how to adapt ancient healing techniques to the unique demands of modern life.

Intro to Chinese Medicine

Yin and Yang: Two Parts of a Whole

The world is made up of opposites: light/dark, empty/full, hot/cold. Neither can exist without the other; each completes the other.

Yin represents darkness, coolness, depth and stagnation. It shows up in the body as the fluids that nourish and cool us. It is commonly thought of as the feminine or receptive side. Menopause and its symptoms of dryness and hot flashes is commonly diagnosed as a deficiency of yin.

Yang is light, hot, external and dispersing, showing up as metabolism and physiological activity. It is stimulating and traditionally masculine. A red-faced angry person about to blow their top is a common picture of an excess of yang.

Yang is light, hot, external and dispersing, showing up as metabolism and physiological activity. It is stimulating and traditionally masculine. A red-faced angry person about to blow their top is a common picture of an excess of yang.

The two are intertwined and reliant upon each other. When yin and yang are in balance, the body is working harmoniously and is in good health. Illness arises from an imbalance of those dualities, and the goal of TCM (simply stated) is to restore that balance.

Qi: The Breath of Life

The concept of qi refers to the vital energy or life force that flows through all living things, maintaining physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health. It can’t be quantified, studied or seen, but its effects are felt when it becomes blocked or stagnant, excessive or deficient. Yin and yang generate and regulate qi.

The Organs: Conceptual Anchors

In TCM, the organs govern both physical and emotional processes. The liver keeps qi and blood flowing, both of which stagnate easily. When the liver qi is stagnant, signs include anger, PMS and headaches. The lungs govern grief, while the large intestine releases physical and emotional waste. The kidneys store our deepest essence and influence growth and reproduction. The spleen, a mash-up of the pancreas and metabolism, governs worry; its qi can become deficient when we multitask, eat on the go or live under chronic stress. Sounds familiar.

My favorite organ is the gallbladder, which is the decision maker. It provides courage and decisiveness. When decisiveness falters, the gallbladder is likely to blame. I think about my gallbladder a lot in the morning as I’m trying to get dressed for work.

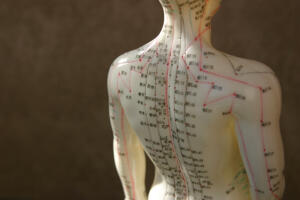

The Meridians: The Pathways

Each organ is associated with a meridian, or conceptual pathway, that runs the length of the body. Picture each path as if it’s on a New York City subway map. One example: the spleen meridian runs from the big toe up through the abdomen to the chest, influencing digestion along its path. This is why a point on the ankle can treat an issue further away, in a different part of the body.

Each organ is associated with a meridian, or conceptual pathway, that runs the length of the body. Picture each path as if it’s on a New York City subway map. One example: the spleen meridian runs from the big toe up through the abdomen to the chest, influencing digestion along its path. This is why a point on the ankle can treat an issue further away, in a different part of the body.

The Points: Nexuses

Acupuncturists use points along the meridians to treat the imbalances they see in their patients. Think of them like a map of the constellations. Out of the 361-plus acupuncture points, some are used more often than others. The point most people are aware of, even if they don’t know it’s an acupuncture point, is called Yintang. It sits right between the eyebrows and is used to calm the mind, settle anxiety and treat minor headaches. As you read this, you can picture yourself instinctually rubbing that spot during times of high stress.

The pulse and the tongue are two powerful diagnostic tools in TCM. The quality of the pulse, not just the rate, and the state of the tongue can tell a practitioner a lot about the body’s energy and stress levels, temperature balance and general status of the qi, or essence.

Food as Medicine

The ancient Chinese made a lot of correlations between food and the way it affects the body. Exploring these ideas is a very easy way to incorporate elements of TCM into your life. Some examples will feel intuitive, while others fly in the face of what we’ve been told for a lifetime, that is, for those of us raised on a Western diet.

In the summer, there’s nothing better than a watermelon, because watery fruits and veggies (count cucumber among them) are thought to cool excess heat. Conversely, herbs and spices like cinnamon and ginger strengthen yang energy and are often consumed during the colder months to generate warmth.

The digestive process in TCM is likened to a fire that must be stoked if dying out and controlled if raging. Foods that are considered “hot” such as chili peppers, increase the fire, which is why some people get heartburn after eating spicy food.

One of the biggest differences between Chinese and Western dietary theory involves the usually uncontroversial salad. In Western diets, people who want to lose weight are often told to eat salad. In TCM, cold, raw foods dampen the digestive fire, leading to sluggishness or weight gain. Warming foods—soups, congee, steamed vegetables—support metabolism. If salads haven’t helped you lose weight, it might be worth rethinking them through this lens.